Hello hello, I hope you’re all doing well. I’m very excited about this month’s recap, mainly because I recently got a deal on a subscription to Mubi so I’ve been trying to be a little more exploratory in the films I’m watching. I also want to address that the January recap sucked and I hated writing it and I’m not proud of it and will probably end up deleting it at some point. I don’t know what happened but I was having really bad writer’s block last month and I was starting to worry that these recaps—which no one reads and I’m basically only doing to challenge myself and give myself a reason to write consistently—were losing juice. I was also getting in my head about feeling pressured to have something to say about every movie I watch, and thus missing out on the pure experience of watching a movie. Luckily I enjoyed writing this one a lot more, and I hope it shows! So without further ado.

Movies

Beau Travail (1999)

dir. Claire Denis

I am endlessly fascinated by and curious about men. I’m specifically curious about the way men experience intimacy with each other. It sounds random or out of character but this is genuinely something I think about a lot. I feel so close to all the women in my life, I have so much affection for them and I have no qualms about expressing that affection, and I feel so much in community with other girls, that I often wonder… do men experience something even remotely similar? Am I being close minded, or is toxic masculinity really that much of an inhibitor to intimacy between men? It’s such a trope at this point that men aren’t in touch with their emotions, that that invulnerability sublimates into anger and violence and aggression and, yes, toxic masculinity. That kind of guy, so impenetrable and out of touch with his emotions, sweating pure testosterone, driven purely by id, is so recognizable in our media nowadays that it’s basically shorthand. When I see a male character written and styled like, say, the guy Patrick Schwarzenegger plays in the new season of The White Lotus1, I feel like I already know what his next words and actions will be, sexed-up, solicitous, and vaguely, menacingly homoerotic. A ticking time bomb that might go off at any moment.

I bring all this up here because this movie is the most unique, poetic, impressionistic, and raw approach to this kind of rugged masculinity, and the destruction it yields, that I’ve ever seen. I’m fascinated by men because I feel like they’re full of tensions and contradictions, which this movie stages breathtakingly. The tension between violence and desire, and how the two are constantly informing and mutilating each other, feels particularly masculine and of particular interest to Denis. The setting for this tension is the French Foreign Legion, stationed in the African country Djibouti, a place completely foreign to these men and thus completely insulating. Amidst sweeping and arid landscapes, retrofit to accommodate the needs of these military men, righteous jealousy and insecurity teems in Sargent Galoup, a man who has dedicated his life not just to the service but to hardening his body and imploding his emotionality to be the best vessel for the “good work” he does. It’s literally written on his body—without this work, he would simply die. A wrench is thrown into this work with the entrance of a new recruit named Sentain, whom Galoup harbors an immediate hatred and rage toward. He never pinpoints exactly where this rage comes from, but the way the camera lingers on Sentain suggests it has something to do with his body, how lithe and loose and beautiful he is, especially in comparison to the rest of the soldiers.2 He’s comfortable in his skin, he’s sensitive. And thus Galoup’s cruel, spiteful mindgames ensue.

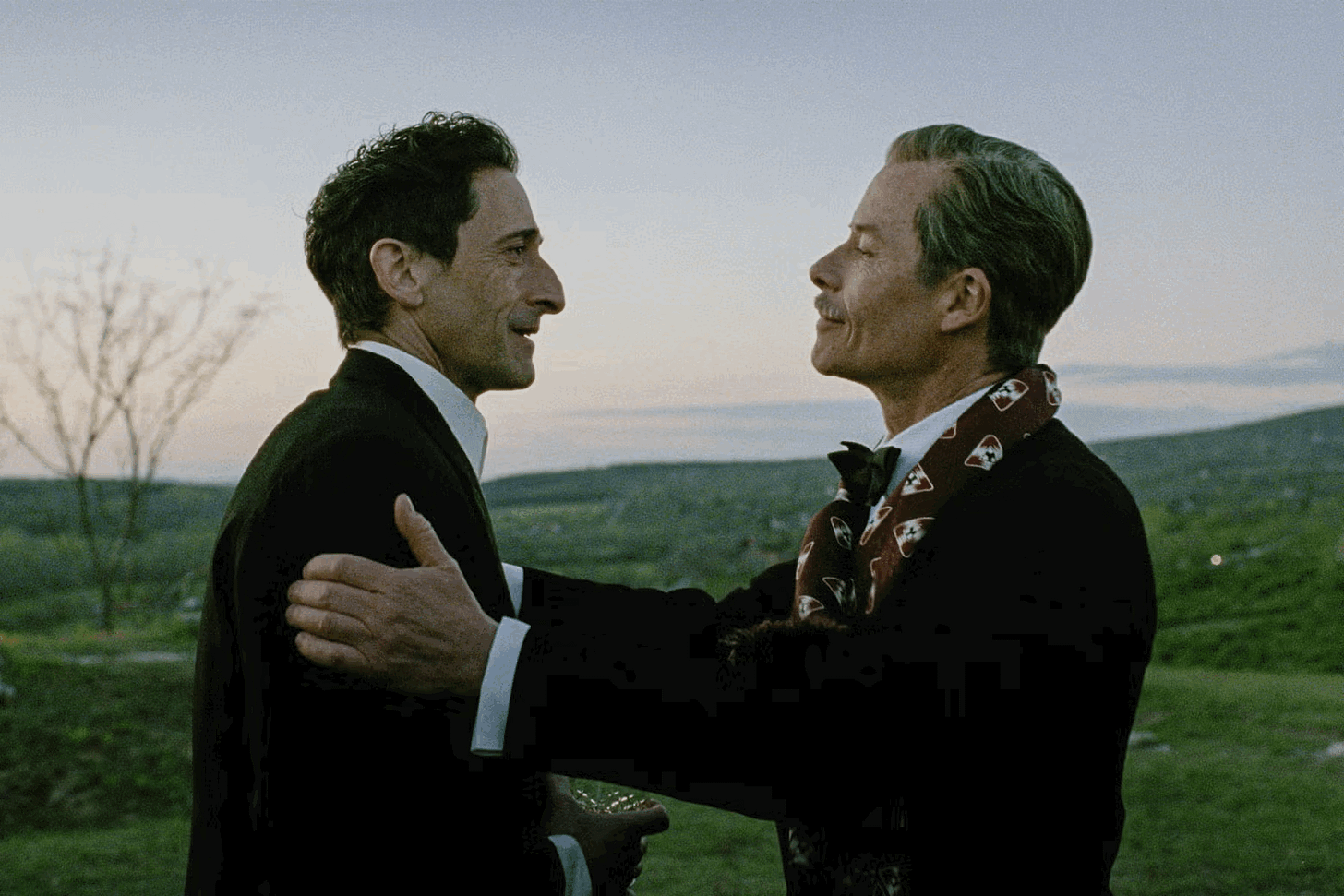

I’ve seen this film classified a lot as a queer film, which didn’t immediately jump out to me, but I suppose this is a queer film in the way that any film about men who envy other men is a queer film, since envy is so inextricably linked to desire. Is Galoup actually just gay, and unable to handle his attraction to Sentain? That’s one way to read it, if a little overly simplistic. I think what makes this movie so hypnotic is that there is no clear answer. When I called this movie “poetic” earlier, it’s because that’s the most apt way I can think to describe it—every shot is so rich and captured so intentionally, and yet you can only make your own meaning out of it. The film lulls you into such a trance that it’s hard to discern what’s actually “happening” most of the time; it’s a feeling, a confusing and often grotesque feeling. In the magnificent final scene, which I wouldn’t dare spoil, so much remains unclear. What actually happened to Galoup? What actually happened to Sentain? Where in the world even are we? It’s unclear, but what is clear is that whatever happened has had a profound effect on Galoup’s body. The final scene, which rests entirely on what the actor manages to do with his body, is oddly moving because of how liberated and unapologetic he finally feels. It’s as if the desire and the violence that has been wracking his body this entire time has somehow found a way to coexist and express itself in this incredible moment, which can only exist out of space and out of time. Overall, I thought this movie was magnificent.

The Brutalist (2024)

dir. Brady Corbet

Ah, where does one even begin when talking about The Brutalist, the new, Oscar ball-playing3, self-avowed American Epic whose three and a half hour runtime (with an intermission!) precedes it. Maybe I’ll start there, at the run time, because it’s the thing that has prompted the most raised eyebrows and disbelieving scoffs whenever I’ve described this movie to people. My opinion may be different from most because I’m someone who actually really enjoys three hour plus movies when they’re well-executed, and, well, this movie is pretty fantastically executed. It didn’t feel like a slog at all. The intermission—and the two act structure that the intermission firmly establishes—definitely helped, but overall I found the movie to be extremely well paced and well edited. (In a group chat, a friend of mine asked why the movie had to be three hours, and another friend replied “cuz it’s a gag for that long” which I have to agree with!)

The biggest consensus among people who could manage the runtime has been that the first act is strong, but that the film kind of falls apart in the second act. I can see where this comes from but that really wasn’t my experience of it at all? I guess my feeling is that the first act felt like it flowed a little more naturally, whereas some of the plot machinations of the second act felt slightly more contrived, and there were certain moments where the commentary was made exceedingly literal. But I never felt like it was “falling apart” per se, and in fact, the intense, traumatic, dark shit that happens in the second act (which is aptly intertitled “The Hard Core of Beauty”) felt like a logical endpoint to some of the idealism of the first act. Not that I would describe anything about this story idealistic, but there’s a certain quality to the first act that feels a little more optimistic and forgiving. It’s not an optimistic or forgiving movie, and the second act, at least to me, felt like the illusion breaking down in a way that I found… satisfying? I guess? I don’t know, people seem to really hate the second act, and I can see why, but I didn’t experience that kind of ire or dread at all.

I think the thing that makes this movie a little annoying to talk about was correctly identified by critic Adam Nayman recently, where he probed at the outsized interest in the meta-narrative of this movie, and whether or not the massive praise has to do with the fact that the production of this movie feels like the accomplishment. I’m guilty of this kind of thinking, because I care too much about the productions of movies that it sometimes clouds my judgement of the movie itself. I think it’s cool as fuck that Corbet managed to make a seemingly uncompromised three and a half hour American epic, which was clearly his vision when he and his co-writer/really hot wife (sick) Mona Fastvold put this story to page. But as for the movie itself, for as swept up in it as I was, and for as much as every new shot stunned me, it wasn’t exactly full of surprises for me? It sets out to be a classic dark-side-of-the-American-dream story, rendered in a massive scale, and it certainly accomplishes that. I felt like I came away with a newfound appreciation for brutalism, something I’d certainly never given much thought to before. I definitely came away with a newfound appreciation for Guy Pearce, who on top of giving a fantastic performance also just seems like a cool guy. But yeah, something about the way the film is being marketed and discussed—particularly as “MONUMENTAL”—is keeping me at a bit of an arm’s length. Maybe that’s where I’m gonna land. Honestly I don’t know. There’s so much to unpack with this movie, maybe I need another viewing. But who has the time… (kidding).

Meeting the Man: James Baldwin in Paris (1970)

dir. Terrence Dixon

This is a deep cut little short documentary that I found on Mubi, about a filmmaker who travels to Paris to interview James Baldwin for a project. Although this film is ostensibly about James Baldwin, it’s just as much about the (white) filmmaker’s inability—and growing frustration with his inability—to neatly distill down Baldwin’s words and ideas into a simple, digestible, placatable package. It’s a really interesting case study in the white desire to simplify and uncritically consume Black art, but above all else it’s as great a testament as any to James Baldwin’s timeless, indispensable words and perspectives.

The Cowboy and the Frenchman (1988)

dir. David Lynch

Another random little gem I came across on Mubi, this one directed by David Lynch! The meat of this is mostly just a bunch of stereotypical jokes about, well, cowboys and Frenchmen, but it feels worthwhile when rendered through Lynch’s absurd humor (and also not-so-absurd—there are a few bits in here that feel like stone-cold classic comedy, as timeless and observable as they come). This contains basically none of his signature ruminative quality—it’s pure comedy, a mode he didn’t dip into very often. I really enjoyed this even if it didn’t leave me much to chew on.

Touki bouki (1973)

dir. Djibril Diop Mambéty

This movie is about a young Senegalese couple who tire of their lives in Dakar and try to set off to Paris, a place that they fantasize about in the aftermath of Senegal’s emancipation from French colonial rule. I think the biggest thing I took from this movie was how it captures the nature of cyclicality in post-colonial cultures. These people are liberated, but also don’t necessarily have the means for upward mobility, nevermind the fact that their vision of “upward mobility” seems to be heavily influenced from the ideas that the colonizers have left behind. They dream of luxuries they could have in Paris, and a jaunty musical cue constantly reminds us of this exoticized idea of Paris, but Paris itself never materializes just like the song never properly concludes. The most interesting aspect of this movie to me was the editing. I was struck by the impressionistic and avant-garde editing and sequencing. Many of these scenes play out as if in montage, and the cuts often feel more intuitive than strictly A-to-B, so much so that there were a few times where I wasn’t sure when or where exactly we were in the story. It constantly felt like the temporality of the story was collapsing. Characters who we knew to exist in one location would suddenly saunter through the frame at an entirely different location, at what we thought was the final destination of the story. This is what I mean by its cyclicality. The scope of the story also feels much smaller than what you initially think, which feels like a cruel twist of the knife by the end. I found this to be a really interesting snapshot of a moment in history that I admittedly know very little about, but even more crucially an energetic, fresh and, dare I say, anti-colonial way of telling this kind of story.

The Fall (2006)

dir. Tarsem

This was another interesting Mubi find for me. I’d never heard of it before but was intrigued after learning more about how this movie has been very inaccessible for a long time, and after seeing the striking thumbnail (pictured below). This movie really leads with its visuals and grandiosity. That’s immediately evident from the highly stylized black-and-white opening credits sequence, to the absolutely massive scale of the later action sequences. Even the hospital where the main story takes place, set nebulously in 1920s Los Angeles, is shot dazzlingly. But the story itself didn’t entirely work for me. It’s a story about storytelling (try not to roll your eyes), and I loved the ways in which this movie collapses the barriers between the story being told to this curious and traumatized young girl, and the real life circumstances of the main characters. This certainly justifies its grandiosity and looseness because the whole movie operates on an infectious sense of childlike wonder. But overall, I didn’t completely buy all the plot beats, nor the character motivations. One of those movies that doesn’t quite hold up under intense scrutiny but is undeniably magical and unforgettable.

The People’s Joker (2022)

dir. Vera Drew

Fuck yeah, this rules. An incredible tribute to how, for a certain type of freak (complimentary), fictional characters and fictional worlds can be of the utmost importance in shaping our identities and better understanding ourselves. And I absolutely love how scrappy this whole thing is. The aesthetic of the film, which consists mainly of barely concealed green screen shots and gloriously low-fi animation, obviously has a classic comic-book feel, but it feels even deeper than that, like someone manically trying to redraw their favorite childhood comic strips from memory and mixing up some of the details. The whole thing is vibrant and rebellious and a little bit brash, but it’s completely sincere in its love for these iconic characters. Even though I’m not trans nor have I ever seen Joker (2019)4, I can relate so much to the experience of rendering yourself through your personal icons. When a film or TV show or book is released into the world, it really does become yours to do whatever you want with. The author is dead, so let’s get a little weird with it! Although, I can see Vera Drew becoming an author who is indispensable to people, if this outstanding debut is any indication. (Also, I have to shout out my absolute favorite joke in this, which is a cheeky Goodfellas reference that you will clock immediately if you’ve ever seen Goodfellas. I screamed out loud at this and had to rewind several times).

Grand Theft Hamlet (2024)

dir. Sam Crane, Pinny Grylls

If you’re scratching your head reading that title, let me set the scene. Amidst the lockdowns in the UK, two out of work actors who pass their time in isolation by playing Grand Theft Auto online attempt to put together a production of Hamlet in the game. I was charmed by this concept and curious to see how it would play out, seeing as I knew literally nothing about GTA other than the fact that all the boys who scared me in middle school were obsessed with it. I don’t know if this works entirely seamlessly as a documentary, mainly because the story beats and emotional moments always felt a little bit too staged. However when the movie is delivering purely on its central concept—rallying other players to audition for this production, location scouting, deliberating over casting decisions—is when it really comes alive. There’s something special in this about the persistence to continue making art despite the odds, and seeing so many people show up for this crackpot idea (in the game and out of the game) was genuinely heartwarming.

Mysterious Skin (2004)

dir. Gregg Araki

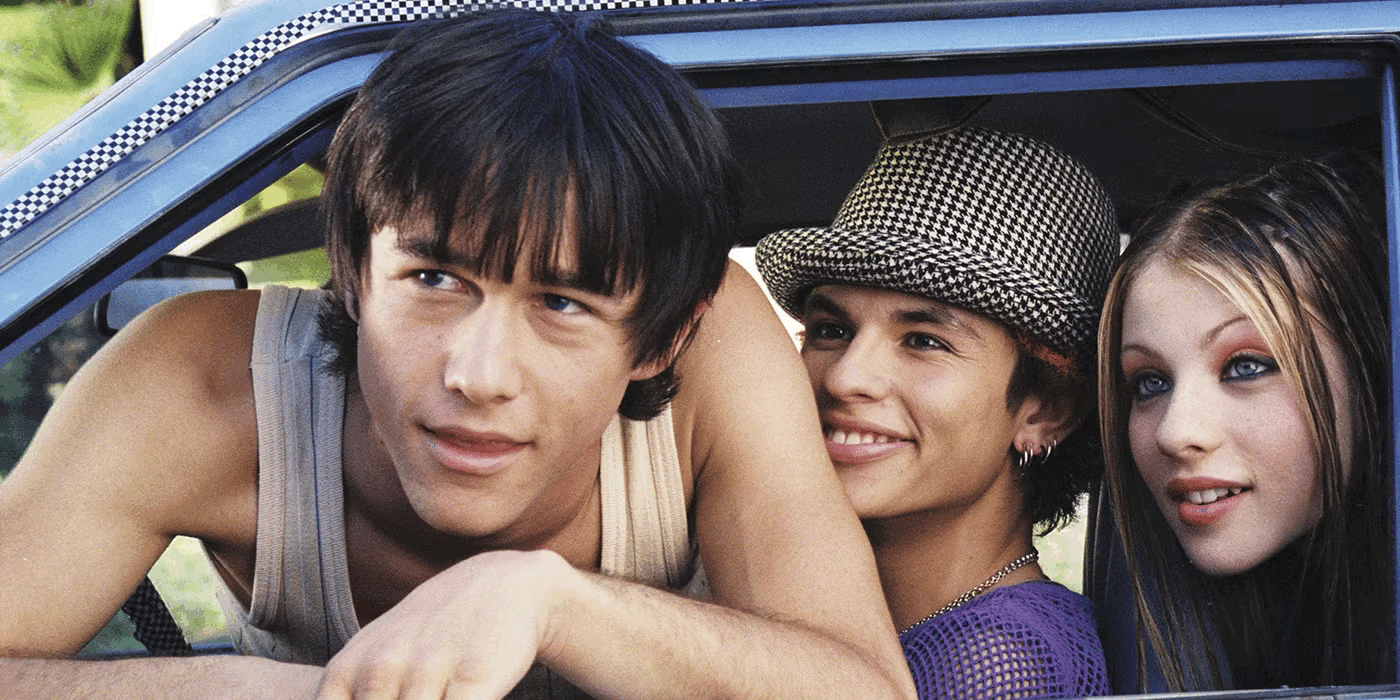

Between Brady Corbet rising to prominence as of recent and the very tragic and sudden passing of Michelle Tratchenberg last week, I wanted to finally dive into this movie that stars the both of them. Gregg Araki has quickly become one of my favorite directors, and this is the movie of his that has been on my radar the longest but has eluded me the most. This is another movie whose reputation precedes it, and I feel like it’s important to say up top, for the sake of the reader, that this movie deals with themes of child sexual abuse and the after affects of trauma in a really unflinching way. It doesn’t beat around the bush in its depiction of that abuse at all, in a way that I can see coming across as distasteful to some (and, of course, downright unwatchable to some), but I have to say I appreciated the choice. I’m not in a position to judge this since I very fortunately have never experienced anything like what these characters experience. However, in my personal opinion, I appreciated Araki’s choice not to shy away from the abuse because I find that sometimes when filmmakers are so evasive of the issue of sexual violence, it can be easy for audiences to turn a blind eye, to brush over it. It can also muddy what the filmmaker is trying to say; their reticence to be blunt with this theme can sometimes read as an unwillingness to fully engage with it or a lack of clarity in the messaging that they’re ultimately trying to impart5. For as uncomfortable as it can be to engage with stories like this (and I certainly hope anyone who relates to stories like this protects their peace above all else, as they aren’t obligated to engage with stories like this), I just don’t think it benefits anyone to skirt around the topic of sexual violence and the long lasting impact that it can have on a person’s life.

And honestly, I feel kind of bad about taking up that whole first paragraph to talk about the scenes of sexual violence themselves, which are a relatively small part of the movie, when the thing that makes the movie so magnificent is how it very tenderly and sensitively—but still without restraint or reticence—shows how this abuse has affected these characters’ lives. The movie employs a dual narrative, one strand following Neil (Joseph Gordon Levitt) who starts turning tricks with older men as a teenager, and the other following Brian (Corbet) who believes that he was abducted by aliens as a child, his explanation for why hours of his life are completely missing from his memory. The way that both of these characters cope, or don’t cope, with what has happened to them is a really intense experience to watch unfold, but Araki does it with grace. One of the things that most affected me was how this movie reconciles Neil’s experiences of abuse with his queerness. It would have been easy to make Neil self-hating because of what he’s been through, or, even worse, to try and sweatily suggest that him being abused as a child somehow “made” him gay. Those are stories we’ve seen before, that are played out and haven’t aged well. I much prefer the route this movie takes: both of these facts about Neil are true and at times irreconcilable, one is always influencing and confusing the other. It’s emblematic of the thing I love so much about how Araki portrays queerness in his films; the characters are never outraged at or resentful of the fact of their queerness, but at the conditions of a world which would dare to suffocate them with such dire circumstances and contrivances. There’s always such a defiant, rambunctious, valiant streak to how he depicts queer characters, and it’s never been more necessary than here.

Overall, this film is bleak and depressing and occasionally horrifying, but there’s also so much tenderness and innocence—and an insistence on innocence—that I deeply admire. For all intents and purposes these characters had their childhoods taken away, and yet Araki still allows them as older teenagers on the precipice of adulthood to experience childlike moments of wonder and discovery and giddiness and joy. Of course these moments make the painful moments sting that much more, but it’s because they’re so real, so human. For as flashy of a filmmaker as Araki can be, and for as visceral as this movie insists very rightfully on being, he has such a profound propensity for humanity that is up there among the best we have.

TV

The White Lotus — season 3

The first episode of this season completely hooked me, and then the two successive episodes have felt a little bit like the same exact scene playing on a loop over and over. I know this show has always operated as a slow burn, but I’m ready for this burn to speed up a bit. But, from what I can tell so far, these character dynamics are some of the most interesting to me of the entire series, and I appreciate the patience and meticulousness with which Mike White sets up these pins so that it’s spectacularly satisfying and delicious when they’re eventually knocked down. The three blonde girlies in particular are fascinating to me– I can’t believe it’s taken this long for a gay guy showrunner to realize that there is no dynamic more biting and potentially toxic than a long time friend who knows both too little and too much about you. But above all else—and I think we can all agree—I’m really happy that this season is turning Walton Goggins into a sex symbol. It’s great to live in a world where Walton Goggins is a sex symbol.

Music

Dear reader, I have just one word, five syllables, five vowels, and six consonants: Abracadabra. We are sooooooo BACK! I will concede that I wasn’t the biggest fan of Disease when it first came out a few months ago. It felt just a little too much like a pastiche of an early Lady Gaga song, without the undeniable, dancefloor-filling hook that defined those early Gaga songs. To be fair, every time I would listen to Disease I would like it more than I remembered from the last time, but overall it didn’t imbue me with that dizzying, “Gaga is so back” feeling that I’d hoped for. But Abracadabra?? Bitch, this shit is in different areas… And the music video?? She’s singing in nonsensical vowels, throwing caution to her hip injury, dancing around in the Margaret Lee Van Buren Center for Creation and Activity. It’s transcendent and it’s pure Gaga, injected straight into the veins. This is what made me say “Gaga is so back.” This is the kind of hype for her new album I’ve been waiting for. I’m awake, I’m activated, and I’m ready to ride. Mayhem is out March 7th. Abra-ooh-nah-nah. Let’s rock.

Books

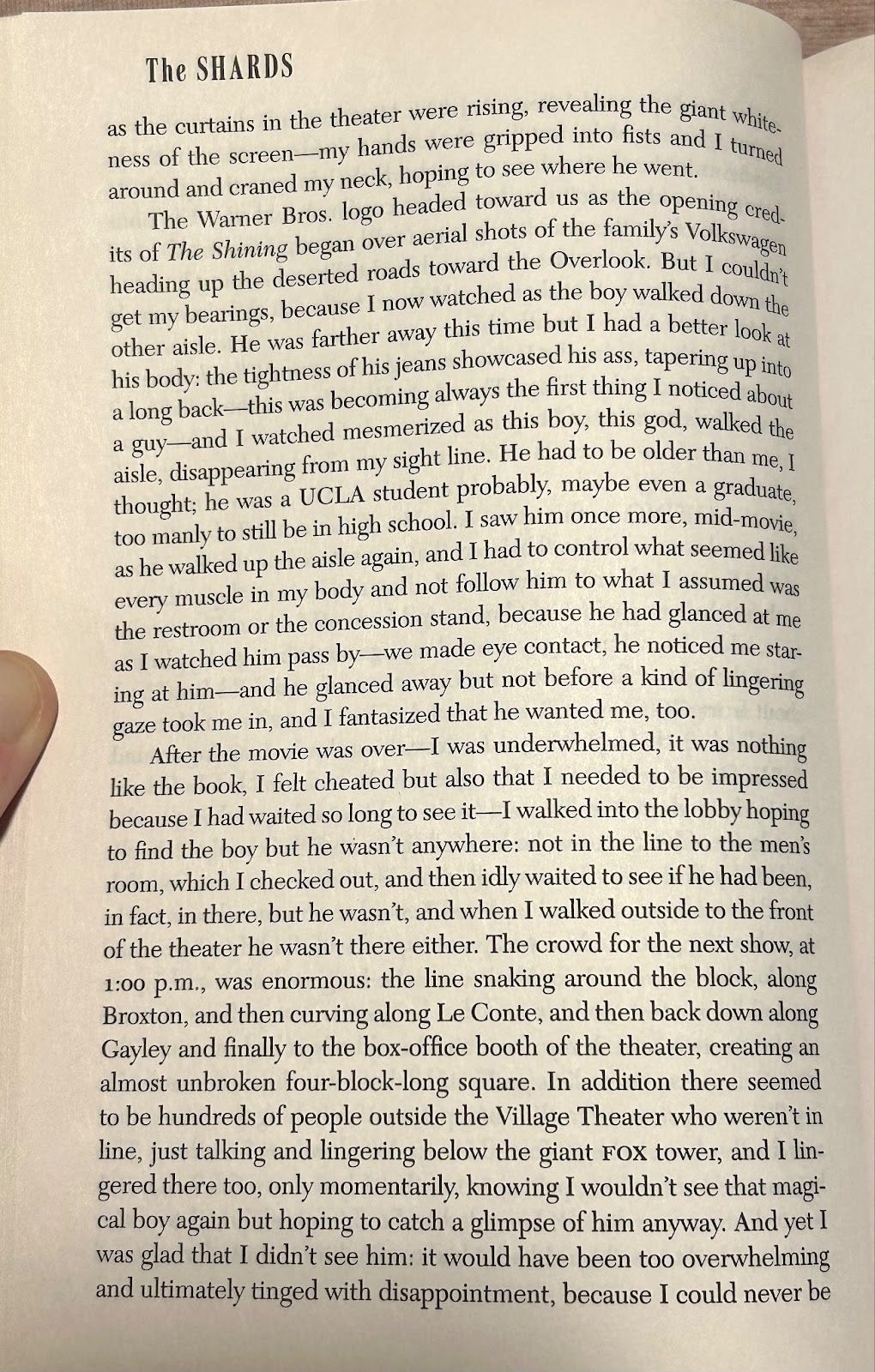

The Shards - Bret Easton Ellis

I absolutely loved this book. It had me completely rapt and I feel inclined to say that it’s a new favorite. Bret Easton Ellis’ style probably isn’t for everyone—both the literal prose style6 and the general air of numbness/remove with which he approaches stories that contain so much violence and brutality—but I’m realizing that it’s very much for me. This particular kind of youthful disaffection, disillusionment, and performative numbness that seems to have defined so many of our teenage years could feel played out at this point, but Ellis does it so well because he basically invented it. Between Less Than Zero and now this book, I think the brooding, washed-out, fetishistic aesthetic that we now lovingly refer to as “2015 tumblr” feels very much a descendent of his particular aesthetic. I basically make this connection to say: every teenager thinks they’re inventing disaffection and remove. And what made this book so fascinating to me (well, one of the many things that made this book so fascinating) is that it’s all about constructing that mask, about trying so hard to go through life completely numb, about teenage Bret (the fictional protagonist) convincing himself that he’s nothing more than a character in a story with a role to play. And in doing this, Bret (the real life author) has to contend with that remove maybe more than he ever has before. The grisly violence, gratuitous sexuality, and near-constant drug use isn’t presented as coldly or cynically or matter-of-factly as it has in the past in his work. It’s pretty horrific, all filtered through the lens of a seventeen year old boy who has at once accepted these things as facts of life and also wishes desperately that he wasn’t the only person being traumatized by all of this.

So much of this book is also very reflexive for Ellis, since the “protagonist” (the most unreliable of narrators) is basically his avatar, a closeted 17 year old boy going to a stuffy private school and living in the upper echelon of Los Angeles. He’s constantly making himself known not just as the narrator but as the author, and collapsing your understanding of what’s real and what’s not. On the same page that he describes the tactics of a fictional LA-based serial killer, he’ll pepper in true facts about where he went to college and what his parents did for work and what year Less Than Zero came out. The denouement of the novel, in which a crucial figure from (fictional) Bret’s past reemerges, takes place at a book signing suffused with so much detail I was convinced this was something that really happened. I’m not sure how effective this would be if you weren’t already a fan of his, but as someone who is avowedly fascinated by not only Ellis’ work but his image and reputation in the literary world, I found this book to be completely absorbing, filled with so many rich details that I was desperately hanging onto. And something tells me this would make for a really rewarding re-read. Without spoiling too much, there was a page early on in the book that I took a photo of because the sheer horniness of the passage that Ellis crafts made me laugh out loud. After finishing the book, I re-read this page, and this passage was suddenly cast in a completely new light, hinging on a single word choice, that made my jaw drop and snapped one of the big “mysteries” of the story right into place. The mystery of the novel was honestly one of its least interesting elements for me, because I hate the feeling of having to look for “clues” and would so much rather just let a story’s themes and dynamics wash over me. But nevertheless, there’s a fascinating serial killer narrative at the center of this that entwines, again, violence and desire in a way that gripped me.

If you want the Cliffs Notes, here is what I wrote about this book a few weeks ago on my close friends story: “my favorite thing about this book so far is that every other page is Bret Easton Ellis going ‘I kissed my girlfriend in front of everyone because I had to keep up the facade that I was straight, then I sat on the bleachers during PE class and read Joan Didion.’ and then the rest of the page is just a Californians sketch of him describing his route to get home. and it’s a masterpiece.”

I loved this book, in fact I didn’t watch many movies in the latter half of this month because I was completely in this book’s clutches. And you better believe that I have a full, detailed list of casting choices for all the main characters, and let me tell you, some of my casting choices are so gagworthy. I pray every day that the adaptation of this book ends up in the right hands (I’m holding out for a miracle that it’ll swing back around to Luca Guadagnino, but God, if you’re reading this, please don’t let it be Ryan Murphy…).

That’s it for February! I feel like there’s quite a bit I left out, particularly on the TV front. This season of Drag Race continues to be solid, and elsewhere Severance is testing my patience a little bit, but I don’t want to take full stock of either of those until their respective seasons wrap up. I also want to write about the Oscars a little more in depth but I haven’t had as much time lately as I would like to write about something so recent. But be on the lookout because that may be coming down the pipeline… maybe… Until then, I will see you all on the other side. Kisses.

Sorry to bring up, of all people, Patrick Schwarzenegger in my review of a Claire Denis movie.

I should note that I don’t know the first thing about military terminology and I’m kind of just taking a shot in the dark for most of this review.

Okay so obviously I wrote this before the Oscars. On that front I will say: I’m happy it won cinematography, thank god it won score (if Challengers couldn’t, obviously), and Brody wouldn’t have been my first choice for actor but considering it was basically between him and Timothée… I’m sorry to say that I’m very content with the result. We all know how I felt about A Complete Unknown.

The highest praise I can give this movie is that it almost makes me want to watch Joker (2019). Almost.

This is a bigger conversation that this little footnote certainly isn’t the venue for, but I think this is also the main problem I have with how Gen-Z has become over reliant on, to the point of basically fully incorporating into everyday language, cutesy little TikTok-friendly censored words and phrases to describe anything remotely distasteful, particularly things relating to sexual violence. I don’t know how to express this thought without just sounding flippant and borderline boomer-ish, but I have to roll my eyes any time anyone unironically says “grape” as a stand-in for “rape,” or the fact that the phrase “SA” and “SA’d,” and that in turn becoming “essay,” is now the go-to way to describe any form of sexual violence, essentially turning it into an easily digestible and understandable monolith, which it of course isn’t. I just don’t think this kind of language helps anyone talk about these things in a more mature or productive way. And not to be a bitch and undermine the very serious point I’m trying to make but I think if you unironically talk this way you’re an idiot…

Which, in the case of this book, includes many blunt statements and run-on sentences, a quirk of the writing that I thought might be the result of him being of such a high stature that he would kind of have carte-blanche to write this book in any way he wanted, but which I later concluded might be a byproduct of the fact that this book apparently originated as a series of spoken excerpts delivered on his paywalled podcast… this man is one of one.